Click here for a full-size map.

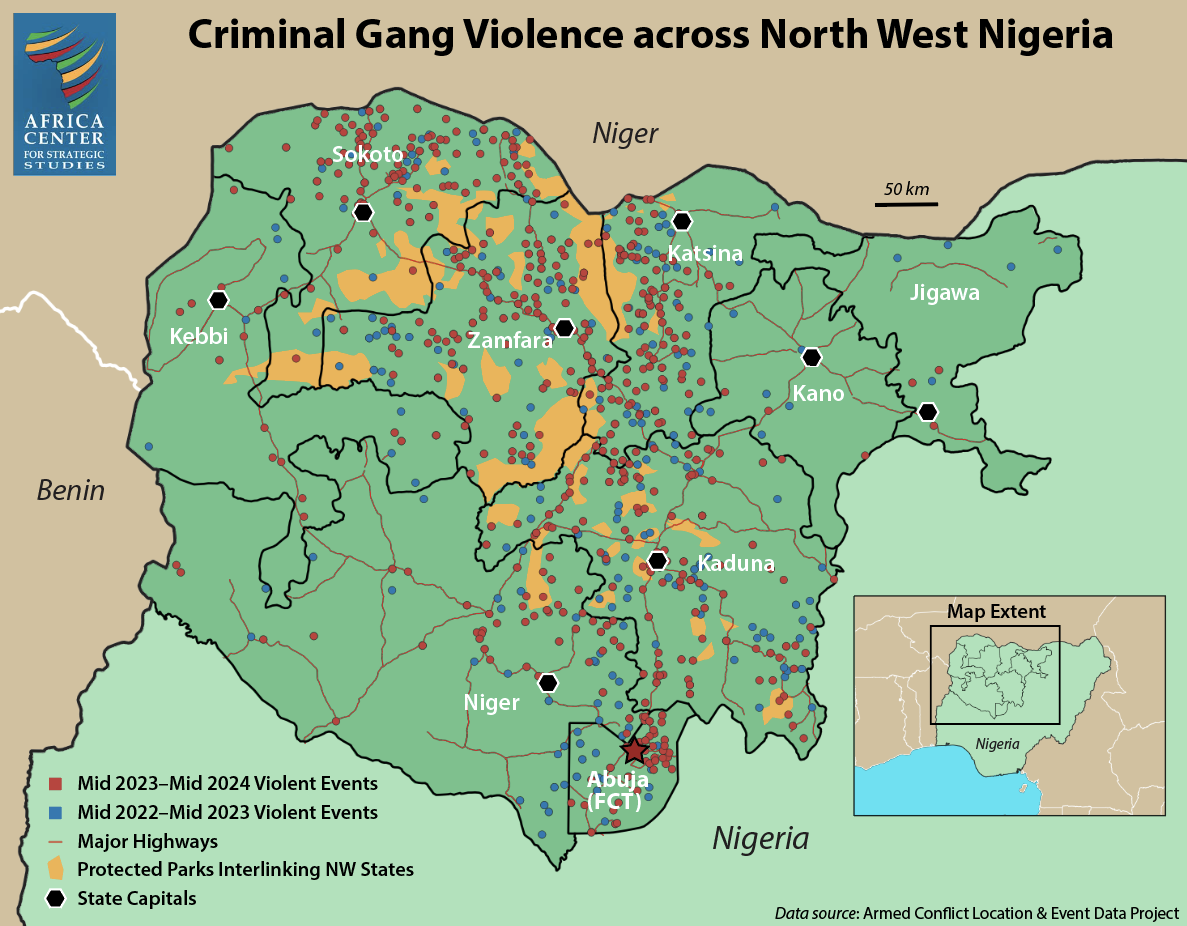

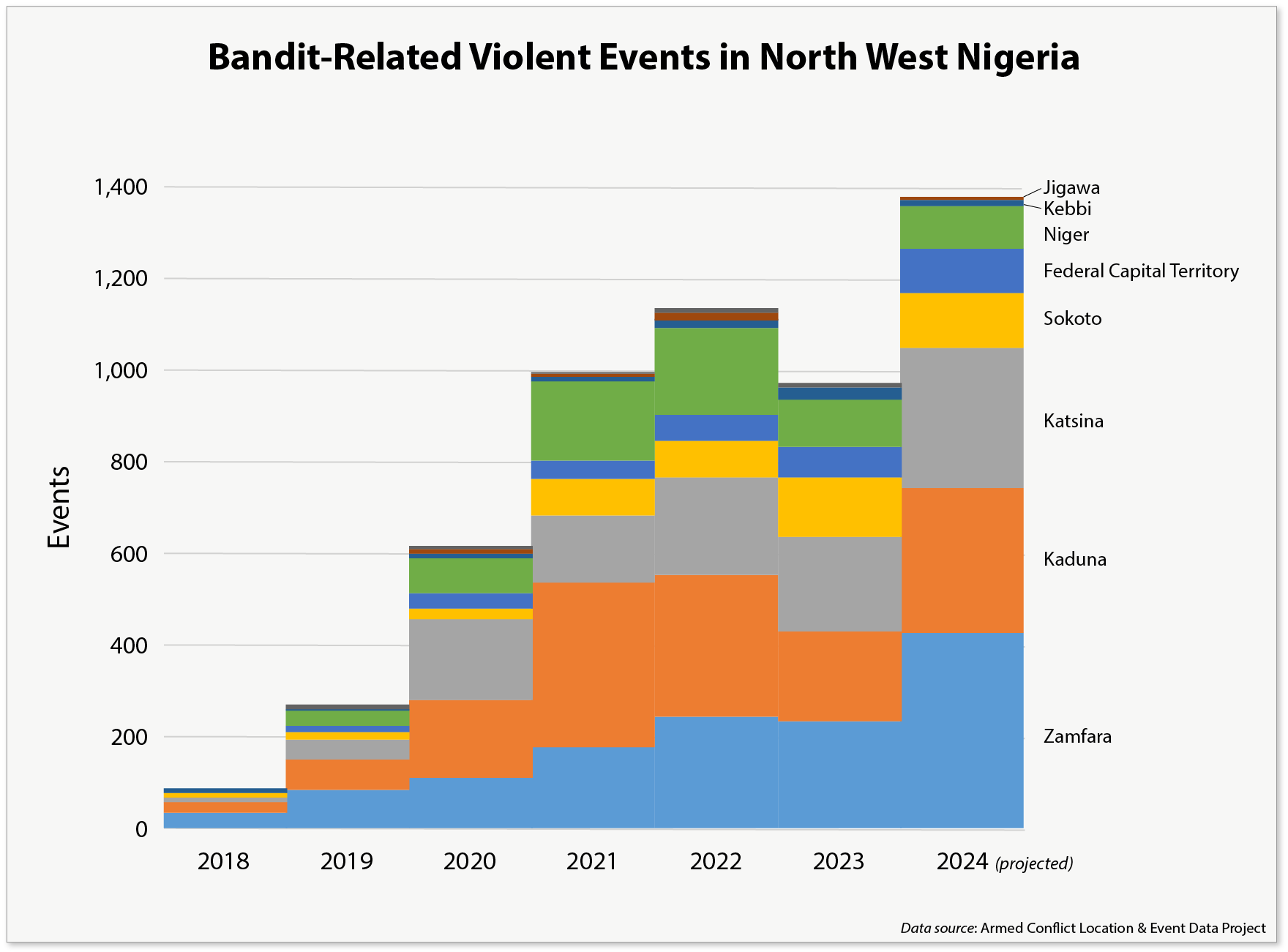

The escalating violence of criminal gangs in Nigeria’s North West region has triggered growing instability in this ethnically diverse breadbasket of some 60 million people. The violence perpetrated by these criminal gangs, known locally as “bandits,” is on pace to make 2024 the worst year of insecurity in the region’s recent history. The 1,380 violent events and 3,980 fatalities projected for the year exceed the record levels observed in 2022, following declines in 2023. Fatalities linked to criminal gangs in the North West region now exceed those tied to militant Islamist groups in the North East region, a shift observed since 2021.

An estimated 84 percent of fatalities linked to criminal groups in the North West region were concentrated in Zamfara, Katsina, and Kaduna States—straddling the heart of the region. These attacks include the targeting of larger urban areas, including the federal capital of Abuja, which saw a doubling in the number of fatalities (to 112). Though rising, this still only represents 3 percent of the total for the region. The escalation in violence on municipalities has led to the temporary shutting down of three local governments and nine villages and towns in Zamfara State alone.

Motivated by the aim of controlling revenue flows, these violent criminal groups threaten communities through robberies and extortion along roads, kidnapping for ransom, cattle rustling, and exploitative agriculture and mining activities. These armed groups have abducted and killed an estimated 9,200 civilians in the region since 2019 when the criminal gang violence first started ramping up. In the process, they have destroyed hundreds of commercial, economic, and farming enterprises.

There are over two dozen major criminal groups and hundreds of small outfits, operating under differing leadership and command structures across the six states (plus the Federal Capital Territory surrounding Abuja). Estimates are that there are over 30,000 bandits active in the region. Even though they sometimes call on God during attacks or while making propaganda videos, the criminal gangs in the North West do not discriminate against their targets based on religious affiliation.

As part of their evolving violent tactics, criminal groups in the region have increasingly turned to seizing farms, which has directly impacted agricultural production. States in the North West region have some of the highest share of agricultural households in Nigeria, including Kano (first), Kaduna (second), Katsina (fifth), and Sokoto (eleventh).

Roughly 700,000 people in the North West region have been displaced due to this insecurity.

An Evolution in Tactics

These gangs initially edged into criminal activities through cattle rustling and small-scale kidnapping but have subsequently moved into massive kidnapping for ransom plots and seizing farm and mining activities.

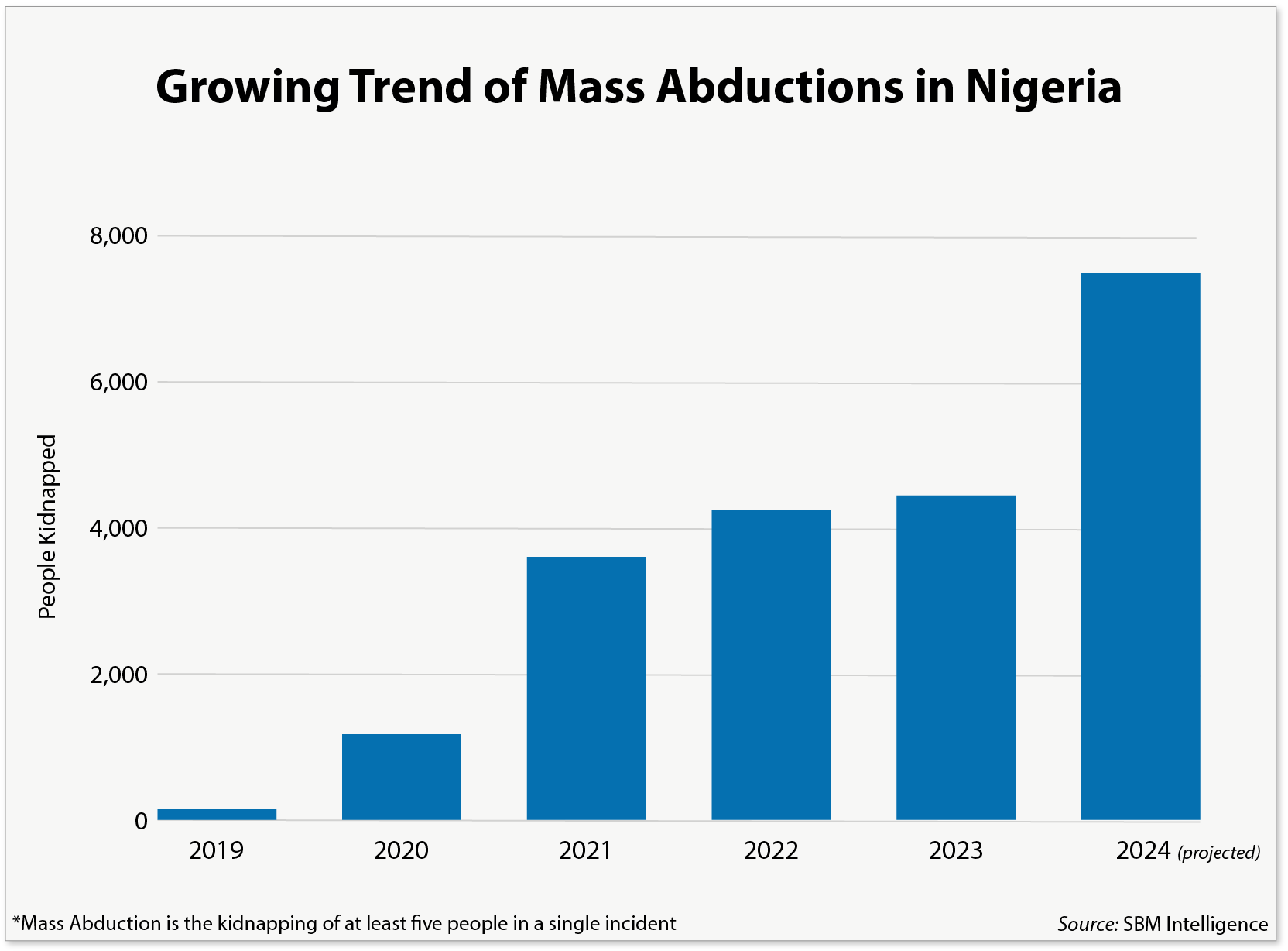

To remedy the shrinking cashflow from individual abductions, the bandits have increasingly turned to mass abductions, targeting over 80 or 100 people at a time, typically at schools or community events. The number of mass abduction incidents (where five or more people are abducted at a time), as well as the number of victims, have steadily increased since 2019. In 2024, the number of people abducted in such attacks more than doubled to an estimated 7,400 people. There has been the equivalent of one mass abduction per day in the country over the past year. The North West region has been worst hit by far with nearly two-thirds the number of victims as the other regions combined.

Mass abductions also tend to attract the attention of the press and, by extension, the government, which expands the pool from which ransoms could be paid. The government insists it does not pay ransoms, but there is evidence that it has continued to do so, especially when the victims are schoolchildren.

These and other tactics have bled communities dry and have shut down economic and political activities in parts of the North West region, making it harder to extract profitable ransoms. This has created panic in the region, which the bandits exploit by levying “protection” taxes on communities. Some villages in Sokoto and Zamfara, having lost confidence in the government’s ability to come to their aid, are paying protection money to the criminal gangs that runs into millions of naira (equivalent to thousands of dollars). Those who default on payments are attacked.

The first recorded farm invasion occurred in July 2022 in Zamfara State, when bandits invaded a farm and killed 11 farmers. Since then, the practice has rapidly escalated. In other instances, the bandits impose a levy on the farmers as a way of increasing revenue generation. While this practice has been around, it has escalated in the last 2 years with a spike in the frequency and sums of these extortions—exceeding what most farmers can raise, exposing them to violent attacks and abductions.

Bandit groups are similarly using villagers as forced laborers on their farmlands at gunpoint.

As a result, a growing number of farmers have abandoned their land. The criminal groups have now established bases in the remotest parts of Zamfara, Sokoto, and Katsina States, displacing locals and taking charge of farming activities. Bandit groups are similarly using villagers as forced laborers on their farmlands at gunpoint. Notorious bandit leader, Zamfara’s Dogo Gudale, was well known for using both tactics.

Some of the more experienced bandit leaders have transitioned into illegal gold mining. This follows a previous transition from cattle rustling to kidnapping between 2019 and 2021, due to the reduced profitability of the former criminal lifestyle. These groups often forcefully take over existing mining operations. Gang leader Halilu Sububu, for example, controlled mining sites in the Bagega community of Zamfara and abducts villagers to work for him. Sani Black adopted the same approach in the Tunani and Daka communities of Zamfara. As with the farms, these criminal groups may extort miners by demanding a share of the profit from their operations.

There are also growing instances of criminal gangs invading communities, killing the residents, and burning their houses because the gangs believe the community is giving information about their hideouts to security forces.

Competition over limited resources has led to increased infighting among the various gangs. This includes Kachalla Dankarami Gwasa versus the late Sani Dangote and Bello Turji. There have also been reports of fights between Ansaru and Dogo Gide’s camp in the Birnin Gwari area of Kaduna, where Ansaru reportedly seized Gide’s mining operations and clashed with his forces.

Growing Humanitarian Costs

Attacks by the criminal groups have resulted in scores of health workers being abducted, medical supplies looted, and many healthcare facilities razed or occupied in states like Katsina, Kaduna, and Zamfara. At times, bandits attack these health facilities to steal medical supplies to treat sick comrades when they are wounded in attacks.

Insecurity has also forced some facilities to shut down because of the risks to medical workers. For nearly 2 years, dispensaries in Zurmi, Maru, Bungudu, Tsafe, Birnin Magaji, Gusau East, and Shinkafi local governments have not been working, and accessing healthcare at the local level in those communities has disappeared. Now, when people in North West region need medical attention, they are usually forced to travel down to the local government metropolis, the state capital, or even a neighboring state.

In the earlier mentioned local governments, schools have been shut for more than 2 years due to the worsening insecurity caused by the activities of bandits. In Zamfara State alone 168 schools remain shut. Bandits instead hold ceremonies or meetings in the evicted schools.

Victims of bandits outside a health clinic in Sokoto, Nigeria. (Photo: AFP / Pius Utomi Ekpei)

The instability caused by the criminal groups is responsible for 100 percent of the population displacements observed in Zamfara and Niger States, 87 percent in Sokoto, 84 percent in Katsina, and 50 percent in Kaduna.

This displacement has a direct impact on food security, as agriculture is the mainstay of the economy in many of these states. The slogan of Zamfara is even “farming is our pride.” Vast expanses of farmlands have become inaccessible or deserted due to displacements, producing very little output. Where people can farm, a substantial portion of their harvests go to the criminal groups.

The impact on output is causing spikes in food prices as well as food shortages. This has contributed to Nigeria having more people who are food insecure than any country in Africa. Estimates are that at least 13.5 million people face acute food crisis in the North West region, including 460,000 confronting emergency levels of food insecurity.

Sustaining a Security Presence

The escalation of criminal group violence in the North West region is directly linked to the inability of the states and federal government to harmonize their efforts to sustain a security presence—providing a vacuum for the criminal elements to exploit.

The escalation of criminal group violence in the North West region is directly linked to the inability of the states and federal government to harmonize their efforts to sustain a security presence—providing a vacuum for the criminal elements to exploit. When present in sufficient numbers, the military has been able to regain control over contested areas. Indeed, fatalities from battles between security forces and the criminal gangs account for 56 percent of all deaths linked to banditry in North West Nigeria. The challenge has been to sustain this presence as there is a high demand for security forces across the region—and in various parts of the country.

Security responses are often slow or absent in remote communities. Some critical places are without security checkpoints or police posts. Security deployments are also moved from place to place because of shifting priorities, rendering some communities vulnerable. Resolving these shortages over the medium term will require developing a national strategy to expand, fund, and train state-level security forces, the Nigeria Police Force, and the Nigerian Army. In the meantime, several priority actions can be taken within the North West region.

Reprioritize policing deployments to protect vulnerable communities. State governments need to establish a stronger presence in rural communities. The availability and deployment of well-trained police officers are at a premium. Police officers who are present and gain the trust of local communities are critical for assessing threats and mobilizing effective responses. One way to increase this police presence is to reduce the number of state police officers who are deployed to serve as escorts to VIPs instead of protecting vulnerable communities. Realigning this prioritization and contracting private security firms to protect VIPs would free up officers.

Expand intelligence-driven military actions. Intelligence-driven military actions can take the fight to the strongholds of the armed gangs, degrading their organizational capacity and capability to mount their predatory actions on local communities. This requires the armed forces to work hand-in-hand with police and community groups who are more familiar with the local physical and sociocultural terrain. This coordinated approach can also limit civilian casualties from military actions that would undermine citizen cooperation.

The sustained deployment and patrolling of key transportation arteries in parts of the region by joint police, military, and civilian tactical units have mitigated the insecurity posed by criminal groups, including the incidences of kidnapping.

Sustain local government presence. Criminal groups in the North West region are reviled and lack popular support. Local communities are faced with the choice of cooperating with them or enduring attack. Citizens would welcome an enhanced government presence so that they are not forced to accommodate the criminal groups. Doing so will require more than security forces, including demonstrable government initiatives to address the loss of arable land due to climate change and improve the quality of life in the affected places in such a way that no ethnic group or demographic is left behind.

Strengthen the rule of law. Justice and the adherence to the rule of law is vital to sustaining security in the North West. A key element of maintaining a government presence and building trust is ensuring that citizens can rely on a functioning justice system to resolve disputes. When a crime is committed, the perpetrators must be made to face the law in a reliable and unbiased manner, regardless of their status or origins. The absence of an equitable and effective justice system enables impunity and criminality. Impunity similarly leads people to take matters into their own hands, which fosters a culture of criminality. A functioning system of rule of law also provides a basis for an effective region-wide disarmament program, credibly signaling to deserters that they will be treated fairly, including a rehabilitative and mild prison sentence.

Police in Kaduna State. (Photo: Allan Leonard)

Institutionalize the militia model of securing citizens in rural communities. Given the current shortage of security personnel, the deployment of community militias is widely seen as necessary. While there have been successes with this model under the Multinational Joint Task Force in the North East, the experience of empowering community militias is fraught with the risk of these groups becoming a menace to communities.

Katsina and Zamfara States have recently launched what they respectively call the Community Watch Corps and Community Protection Guards (Askarawan Zamfara). There is also the Vigilante Service in Kaduna and the Community Guard Corps in Sokoto. The initiatives, however, have been criticized for their biased recruitment patterns, lack of adequate training, and insufficient oversight and accountability. Some community militias have been accused of ethnic profiling, cattle rustling, arson, and extrajudicial killings.

Drastic measures are needed to curtail the excesses of vigilante groups who are accused of indiscriminately killing innocent civilians because of their ethnicity. Bandit groups capitalize on anti-Fulani sentiment and attacks to promote the propaganda of victimhood and recruit people who either want to seek revenge or see crime as a way out of the poverty foisted on them by the conflict. Indiscriminate attacks by community militias will also make reconciliation difficult in a post-conflict era. These community security forces, accordingly, must be adequately instructed and held accountable for respecting the rule of law.

Lacking the operational training and arms needed to match the bandits, community militias simultaneously often take heavy casualties at the hands of the criminal groups. To effectively serve as a deterrent against attacks on soft civilian targets, community militias need to be properly trained, equipped, and supported to confront the assailants.

Mr. Kunle Adebajo is a journalist who has reported extensively on the banditry crisis in North West region. Mr. Hamza Ibrahim is a journalist based in Kano who has tracked the growing threat and responses to the security threat firsthand.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Famine Takes Grip in Africa’s Prolonged Conflict Zones,” Infographic, October 15, 2024.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa’s Constantly Evolving Militant Islamist Threat,” Infographic, August 13, 2024.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Delivering on Nigerians’ Demands for Security,” Spotlight, June 5, 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Criminal Gangs Destabilizing Nigeria’s North West,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 14, 2021.

- Mark Duerksen, “Nigeria’s Diverse Security Threats,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 30, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Nigerian State and Insecurity,” Video Roundtable, February 17, 2021.

- Olajumoke (Jumo) Ayandele, “Confronting Nigeria’s Kaduna Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2, 2021.

- Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2016.

- Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.

More On: Nigeria